THE OLD STADIUM in the Bronx—built nearly 100 years ago—closed for business in 2008. The house that Ruth built had been home to the New York Yankees since before the days when their line-up was dubbed “Murderer’s Row.” Ghosts of legends like Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, and Mantle inhabited the place.

But the edifice located at East 161st Street and River Avenue in the Bronx was much more than a baseball park; it was America’s premier outdoor arena. If we were to pick a place that has been to us what the Coliseum was to Rome in days of glory, most would nominate Yankee Stadium, whether they liked the Yankees or not.

Looking beyond the Yankees, and their inseparable relationship with the stadium, we note that the venue provided the backdrop for many sports and cultural events that transcended baseball. From concerts, to religious services, to a national memorial service for victims of horrific terror just twelve days after 9/11, Yankee Stadium has been part of the scenery of American life.

When it comes to sports, the stadium has not just been a place for home runs, but also the field of battle for gladiators of the gridiron and soccer stars.

And, of course, there was the boxing.

It’s been a generation since a championship fight was held at Yankee Stadium (Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton in September 1976), and they were becoming rare events for the venue even then. But during the sweet science’s heyday in the 1920s-1950s, the stadium ring planted over second base was the scene of many epic battles.

It’s been a generation since a championship fight was held at Yankee Stadium (Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton in September 1976), and they were becoming rare events for the venue even then. But during the sweet science’s heyday in the 1920s-1950s, the stadium ring planted over second base was the scene of many epic battles.

Sugar Ray Robinson, often referred to as the greatest “pound for pound” boxer of all time, had already won welterweight and middleweight titles. On a dreadfully hot night in June 1952, he tried to win the light-heavyweight crown against champion Joey Maxim. And he was clearly winning when he succumbed to heat exhaustion in the fourteenth round. He did, though, last longer than the referee, who had been carried out two rounds earlier.

Jack Dempsey, on the comeback trail seeking a rematch with Gene Tunney, fought at Yankee Stadium in 1927. Tunney fought there, too. In fact, there were 30 championship fights held on that field.

Calling something the best, or most significant, is always subjective and therefore risky. But I think I’m right when I suggest that Yankee Stadium’s greatest moment did not involve Babe Ruth or even Reggie Jackson. It wasn’t even a baseball game.

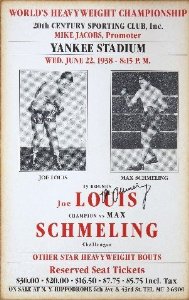

Eight-four years ago, two boxers climbed into the famous stadium’s ring and squared off in the most historic boxing match, if not sporting event, of the decade – maybe the century. Max Schmeling and Joe Louis had fought in the same ring two years before, and the former world heavyweight champion from Germany had somehow, some way, found a flaw in Louis’ style.

The Brown Bomber from Detroit (the Yankees would soon be called “Bronx Bombers” as a take off on Louis’ nickname), as he was called, had been well on his way to pugilistic immortality, easily dispatching opponents—even former champions – hardly breaking a sweat. He seemed to be invincible. But the first fight with Max ended with Joe on the canvas in the twelfth round trying to remember who and where he was.

It was the 1930s and the world was becoming a very ominous and confusing place. Hitler’s Nazi-Germany was on the move, and the dictator was beginning to look invincible himself.

Schmeling, as a German, was blocked from fighting James J. Braddock for the title, even though he was clearly the number one contender. It fell to Louis to fight the Cinderella Man in 1937. Braddock was defending his title for the first time. Louis went down in round one of that fight – only to come back strong and knock Braddock out in the eighth.

Yet, though he was the champion in name, Louis knew that he wouldn’t be able to think of himself that way until he could settle his score with Mr. Schmeling. Most fight fans felt the same way.

In ancient times there was something called representative warfare, where one man from an army would do battle with an opponent sent by the enemy, and the larger conflict would be decided by this “one on one” ordeal. The Philistine giant, Goliath, who taunted the ancient Israelites, proposed this kind of settlement to the issues of his day. Then he met a boy named David.

In 1938, as the world was becoming increasingly polarized in the face of impending war and as it was becoming clear to all people of freedom and good will that the Nazis were evil, the situation was ripe for a representative battle of sorts. And the rematch of Joe Louis and Max Schmeling fit the bill.

So, on June 22, 1938, veteran referee Arthur Donovan gave his ring instructions to two determined boxers as nearly 70,000 Yankee Stadium spectators looked on. More than 100 million radio listeners tuned in from around the world. This was the largest broadcast audience ever up to that time and included just about half of the American public. That morning, the New York Journal-American had a large cartoon in the paper, one that showed a stadium and two figures in a boxing ring. Hovering above the ring was the image of an immense globe bearing the face of a man. He was looking down on the scene on behalf of all humanity.

So, on June 22, 1938, veteran referee Arthur Donovan gave his ring instructions to two determined boxers as nearly 70,000 Yankee Stadium spectators looked on. More than 100 million radio listeners tuned in from around the world. This was the largest broadcast audience ever up to that time and included just about half of the American public. That morning, the New York Journal-American had a large cartoon in the paper, one that showed a stadium and two figures in a boxing ring. Hovering above the ring was the image of an immense globe bearing the face of a man. He was looking down on the scene on behalf of all humanity.

Yes, it was that big of a deal that night.

Author David Margolick, in his definitive account of that evening entitled Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink, wrote: “The fight implicated both the future of race relations and the prestige of two powerful nations. Each fighter was bearing on his shoulders more than any athlete ever had. One didn’t need to be an anthropologist to know there had never been anything like it, or a soothsayer to know there would never be anything like it again. If Louis won, no rivalry on the horizon could possibly generate as much excitement. And with Europe and, inevitably, America, on the brink of war, the world would soon enough have more than prizefights on its mind.”

If you ever get a chance to see a film of the fight that night, try to find the audio of the radio broadcast by NBC’s Clem McCarthy as well. His gravelly voiced blow-by-blow description turns the ear into an eye. Joe Louis was ready this time – he knew what he was fighting for, and he didn’t want to waste any time.

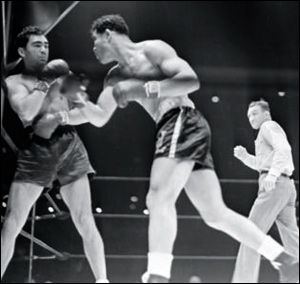

Seven seconds into the bout, Joe Louis snapped the head of his opponent back with a left-jab, then another, and another. Later opponents would suggest that Louis’ jab wasn’t a Muhammad Ali-type punch but more like putting a light bulb against your face, then breaking it. Thirteen seconds later he had Schmeling on the ropes. McCarthy could hardly keep up: “And Louis hooks a left to Max’s head quickly! And shoots over a hard right to Max’s head! Louis, a left to Max’s jaw! A right to his head! Louis with the old one-two! First the left and then the right! He’s landed more blows in this one round than he landed in any five rounds of the other fight!”

You get the picture.

In two minutes and four seconds it was over. But no one felt cheated. There were no catcalls that might usually accompany a lop-sided battle. Referee Arthur Donovan later said: “A referee lives a lifetime in two minutes like that.”

So does a nation.

The rest is history. The defeat of the German in the ring didn’t slow the world’s long slide into war – nor could it have. Louis went on to fight again and again and again, defending his title successfully fifteen more times before December 7, 1941. Schmeling went home in disgrace. Nazis didn’t like it when someone from their master race got beaten up by a black man.

A few months after the fight, on November 9, 1938, as Nazis terrorized Jewish businesses and houses of worship during Kristallnacht, Max Schmeling sheltered two Jewish young people in his hotel suite in Berlin.

Joe Louis served his country in uniform during the war and emerged after to continue his career, though the clock was running out on his days of glory. He died in 1981. His former foe helped pay the cost of Joe’s funeral. Max Schmeling, who lived to be just seven months shy of a hundred years old, died in 2005.

Their brief, but explosive meeting in June 1938 at Yankee Stadium captured the attention of the world and the imagination of our nation. So, the great ballpark should be remembered as a place for more than baseball.

Yankee Stadium was a field of dreams, history, and glory.

What’s your favorite Christmas song?

What’s your favorite Christmas song?